NASA has achieved great success with its Ingenuity Mars helicopter, exceeding its original mission goals. Based on their learnings from this groundbreaking Mars helicopter, NASA is now working on an even more complex flying machine to explore Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

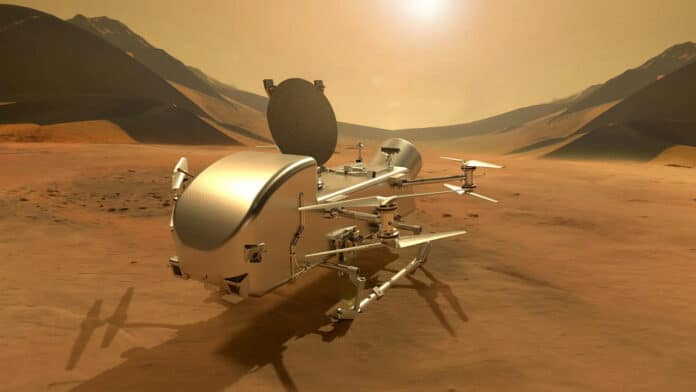

Dragonfly, NASA’s only mission to the surface of another ocean world, is designed to investigate the complex chemistry that is the precursor to life.

Unlike Ingenuity, with a single rotor and a height of just 19.3 inches, the Dragonfly rotorcraft features eight rotors and is the size of a small car. But Titan’s dense atmosphere will make it easier to fly in than Mars’ considerably thinner atmosphere. The low gravity of Titan also helps the machine stay in the air for longer periods of time.

The vehicle will have various instruments on board to examine swaths of Titan known to contain organic materials that may, at some point in Titan’s complex history, have come in contact with liquid water beneath the organic-rich, icy surface. These include cameras to capture images, sensors to measure physical properties, and samplers to collect and analyze samples.

To fly in Titan’s thick, nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, Dragonfly has four pairs of coaxial rotors (meaning one rotor is stacked above the other).

Well before this nuclear-powered Dragonfly rotorcraft lander soars through Titan’s skies, a team of researchers led by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland is making sure their designs and models for the drone will work in a truly unique environment. The mission team has been paying regular visits to NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, to test out Dragonfly’s flight systems inside the facility’s various wind tunnels. The data collected from these tests helped the team optimize the aircraft’s design.

The Dragonfly team has performed four experiments in two wind tunnels at NASA Langley. The 14-by-22-foot Subsonic Tunnel helps them validate computational fluid dynamics models and data gathered from integrated test platforms – terrestrial drones outfitted with Dragonfly-designed flight electronics.

They used the variable-density heavy gas capabilities of the 16-foot Transonic Dynamics Tunnel to validate its models under simulated Titan atmospheric conditions. They performed one test to check the stability of the aeroshell that is used to deliver the Lander to a release point above Titan’s surface and another to study the aerodynamics of the Lander’s rotors.

On its latest trip to NASA Langley, the team tested a half-scale Dragonfly lander model, complete with eight rotors, in the Subsonic Tunnel. The campaign was focused on two flight configurations: Dragonfly’s descent and transition to powered flight upon arrival at Titan and forward flight over Titan’s surface.

“We tested conditions across the expected flight envelope at a variety of wind speeds, rotor speeds, and flight angles to assess the aerodynamic performance of the vehicle,” test lead Bernadine Juliano of APL said in a release. “We completed more than 700 total runs, encompassing over 4,000 individual data points. All test objectives were successfully accomplished, and the data will help increase confidence in our simulation models on Earth before extrapolating to Titan conditions.”

Dragonfly is scheduled to launch no earlier than 2027 and arrive at Titan in the mid-2030s. “With Dragonfly, we’re turning science fiction into exploration fact,” said Ken Hibbard, Dragonfly mission systems engineer at APL. “The mission is coming together piece by piece, and we’re excited for every next step toward sending this revolutionary rotorcraft across the skies and surface of Titan.”