As we peer into the vast expanse of space, researchers and engineers are constantly pushing the boundaries of innovation to do more with less. Current small spacecraft are equipped with sensors, guidance, control systems, and operating electronics integrated into every available space. Scientists are experimenting with printing electronic circuits directly on the walls and structures of spacecraft. This could help future missions achieve even more with even smaller packages.

Recently, aerospace engineer Beth Paquette and electronics engineer Margaret Samuels of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center successfully tested hybrid printed, electronic circuits at the edge of space. The experiment sought to prove the space-readiness of printed electronics technology.

The space-readiness test was demonstrated by the Suborbital Technology Experiment Carrier (SubTEC-9) sounding rocket mission that reached an altitude of about 108 miles (174 kilometers) before descending by parachute into the Atlantic Ocean to be recovered.

The test consisted of electronic temperature and humidity sensors printed onto the payload bay door and onto two attached panels, which monitored the entire SubTEC-9 mission, recording data that was beamed to the ground. The collaborative effort undertaken for the project was a success and holds the potential to help scientists and engineers improve design efficiency for smaller spacecraft.

“The uniqueness of this technology is being able to print a sensor actually where you need it,” Samuels said. “The big benefit is that it’s a space saver. We can print on 3-dimensional surfaces with traces of about 30 microns – half the width of a human hair – or smaller between components. It could provide other benefits for antennas and radio frequency applications.”

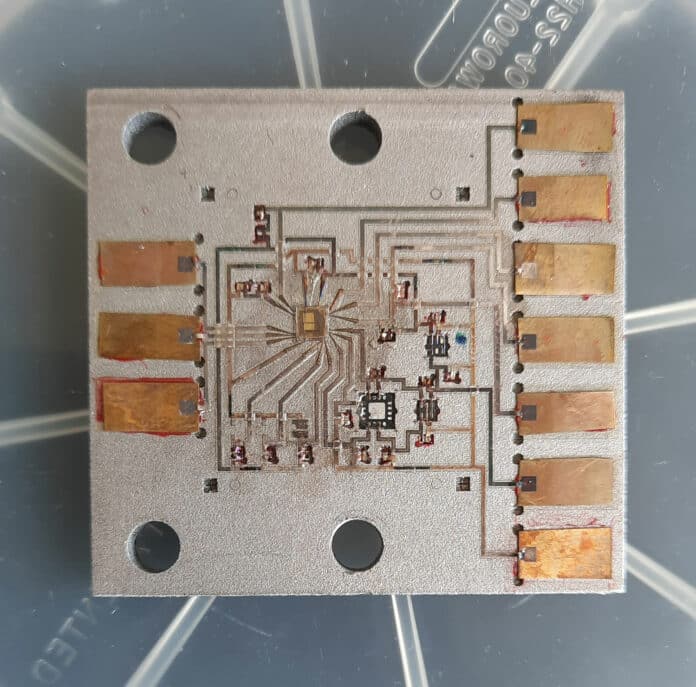

Colleagues at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, developed the humidity-sensing ink, while partners from the University of Maryland’s Laboratory for Physical Sciences (LPS) created the circuits.

Wallop’s electronics engineer Brian Banks stated that printed circuits allow a new level of functionality for smaller spacecraft, ever more common for both near-Earth and deep space missions. “The hybrid technology allows for circuits to be fabricated in locations that would typically not be available for conventional electronics modules,” he added. “Printing on curved surfaces could also be helpful for small, deployable sub-payloads where space is very limited.”

LPS engineer Jason Fleischer designed and printed the circuits for the flight using printers capable of producing electronic traces thinner than the human eye can see. Engineers have printed electronic circuits on a variety of materials, including around curves and corners and on flexible parts. In another experiment, they also printed X-ray instruments on flexible strips of Kapton plastic.

Paquette said future missions could print temperature sensors throughout the vehicle’s interior surfaces. For a small investment, such a mission could better understand how heating and cooling affect the whole spacecraft as it passes close to the Sun, for example.

Along with testing the 3D-printed electronic circuits, the SubTEC-9 mission is a test flight used to test 14 new technology development experiments that enable new capabilities for the science community. This includes a new star tracker, a faster telemetry link, ethernet-based components, a low-cost gyro, a new antenna, and a new high-density battery.