Perovskites have great potential for creating solar panels that could be easily deposited onto most surfaces. These solar cells can match silicon for efficiency, are cheaper to manufacture, and are more flexible, but they haven’t become commercially viable yet, because they’re still too unstable when exposed to heat, light, moisture, and oxygen.

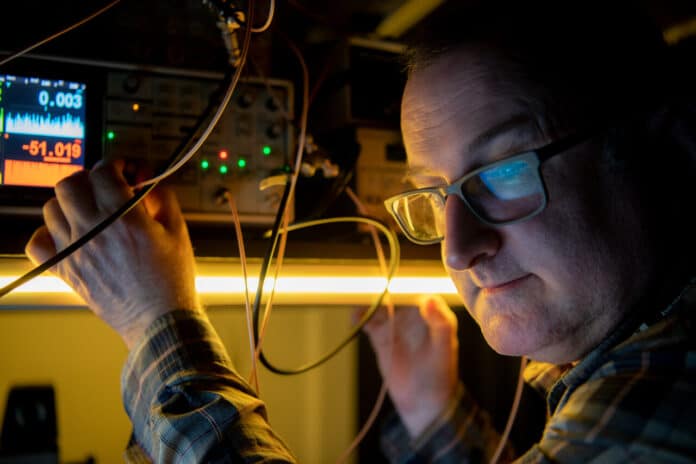

That’s where Dr. Jamie Laird’s device comes in. The Research Fellow at the ARC Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science and the University of Melbourne has invented a new machine for testing the defects in perovskite solar cells, the first of its kind anywhere in the world. The do-it-yourself device started life as a hobby and took off during COVID-19. It could help to unlock the next generation of solar energy, including advanced technology for space missions.

The device is a combination of a microscope and a special laser that produces pictures and maps of the defects within solar cells and tells scientists where the cells are losing power or efficiency over time and use. It also provides data to indicate why.

The innovative technique was solely meant to be a personal project for Jamie and was originally intended to analyze minerals. But when he joined Exciton Science, Jamie realized his device would be a perfect tool to help colleagues and other leading solar cell researchers around the world to better understand the frustrating issues that have kept perovskites from fulfilling their exciting promise.

“The basis of the technique is microscopy but merging it with frequency analysis,” Jamie said. “We use a laser beam, and we focus on a spot and scan across the device to measure the quality of the solar cell. This new method allows us to do imaging analysis of whole or complete solar cells and look at how they perform, how they change with time and aging, and how good a solar cell they are.”

The partners at Monash University and Oxford University are already sending samples of cutting-edge prototypes to be tested by Jamie’s homemade machine. And the team at the University of Sydney working on experimental solar cells for satellites and other space vehicles is also on the waiting list to collaborate.

“You can’t have a solar cell that decomposes quickly when it’s meant to last 20 years in the field,” Jamie said. “This is a missing link in the repertoire of techniques we have to throw at that problem.”