Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) has released a series of rare and never-before-seen images of Colossus in celebration of the 80th anniversary of the world’s first digital electronic computer that played a pivotal role in the Second World War effort.

During the Second World War, the Colossus computer was created to decipher critical strategic messages exchanged between the most senior German Generals in occupied Europe. Its existence remained hidden from the public eye for over six decades until the early 2000s.

Although planning for the D-Day landings was already underway when Colossus was introduced, it was one of the machines that helped produce the intelligence that convinced Hitler that the Allies would be launching the invasion from Pas De Calais and not Normandy.

Unlike the well-known Bombe Machine, which broke the Enigma cipher, the existence of Colossus was kept from the history books for almost six decades. Engineers and codebreakers who had worked on Colossus were sworn to secrecy, and after the Second World War, eight out of the ten machines were destroyed.

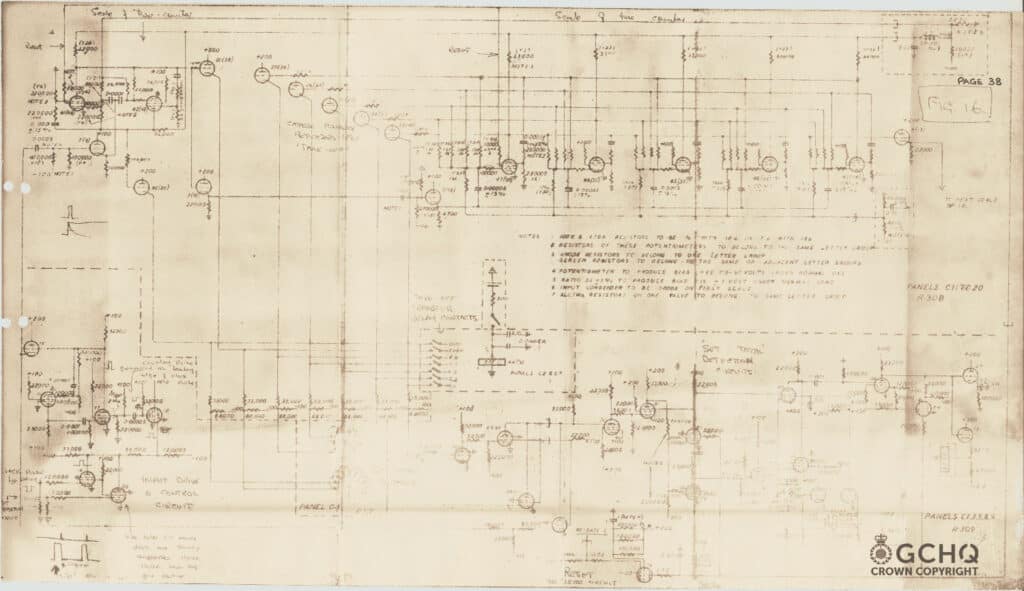

Tommy Flowers, who designed and oversaw the development of Colossus, was ordered to hand over all documentation on the build to GCHQ. This was partly because the technology was so effective that its functionality was still in use until the early 1960s. At Bletchley Park, where the computer was installed, only a small group – all sworn to the Official Secrets Act – knew about the work being done with Colossus.

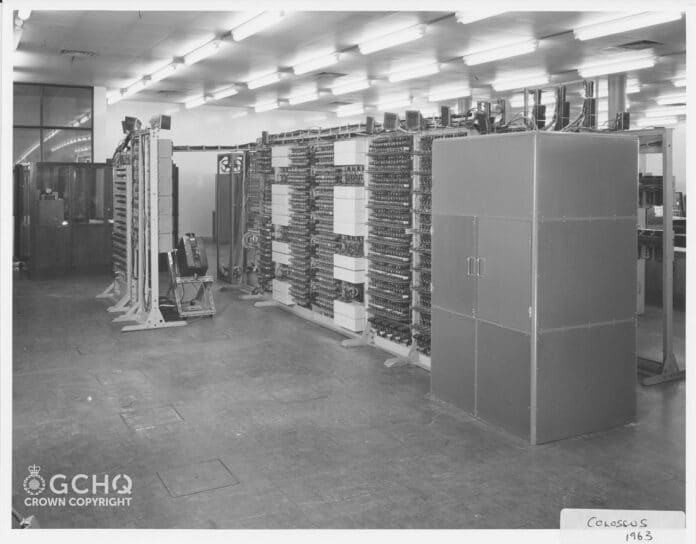

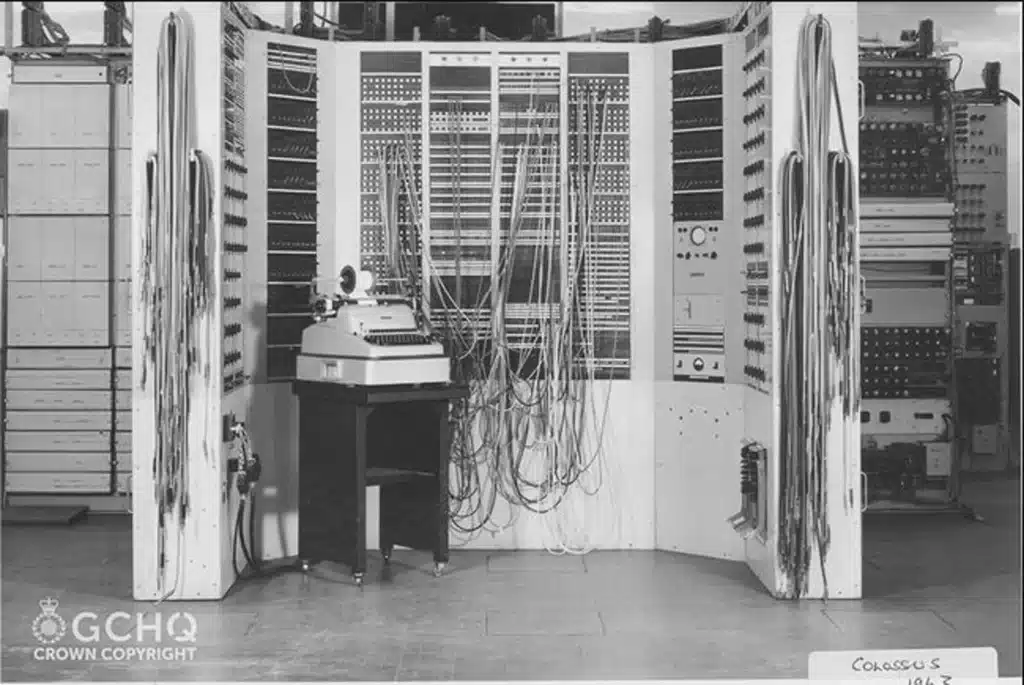

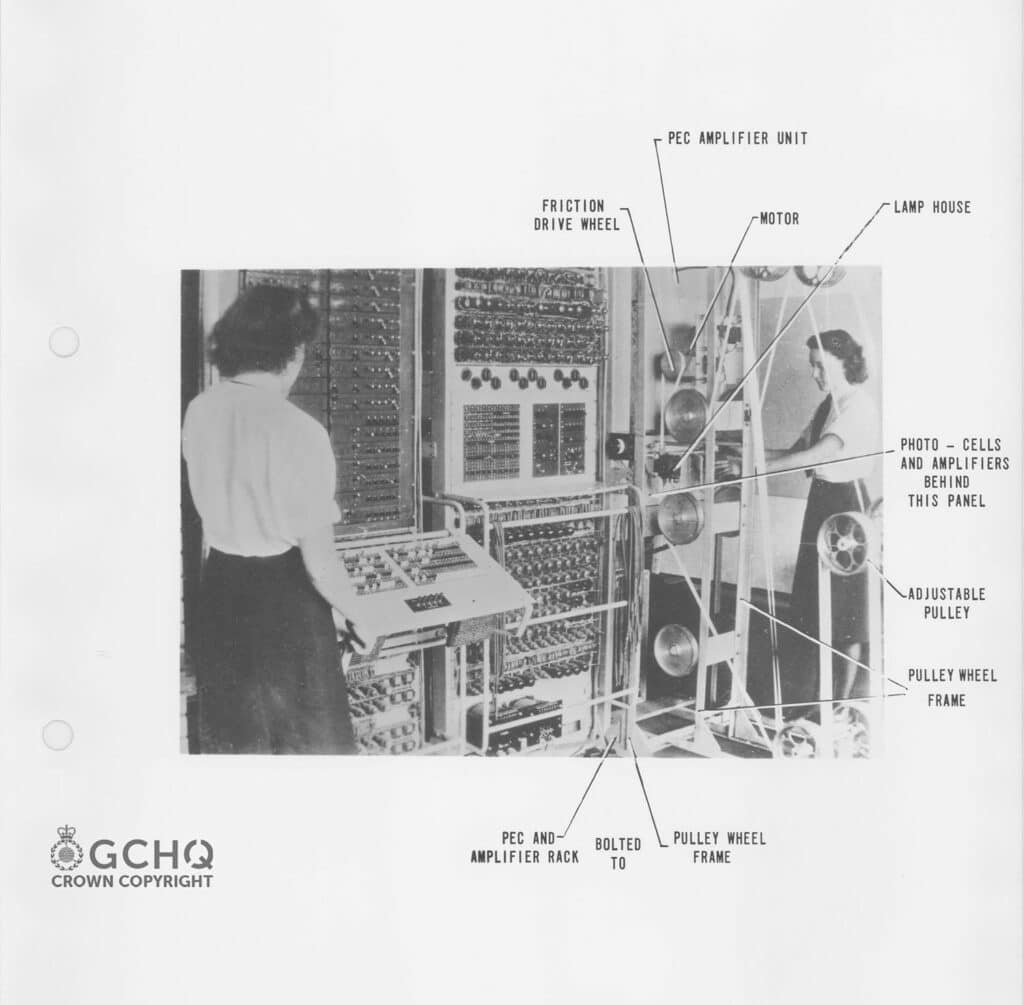

The newly released images shed new light on the genesis and workings of Colossus, which is fitted with 2,500 valves and stands more than 2 meters tall. It required a team of skilled operators and technicians to run and maintain it. The machine was considered by many to be the first-ever digital computer.

The images include new pictures of Colossus as well as of the Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service) who attended it. The security was so tight that the women had no idea what the machine was doing. Even the technicians tasked with building and repairing it had no clue.

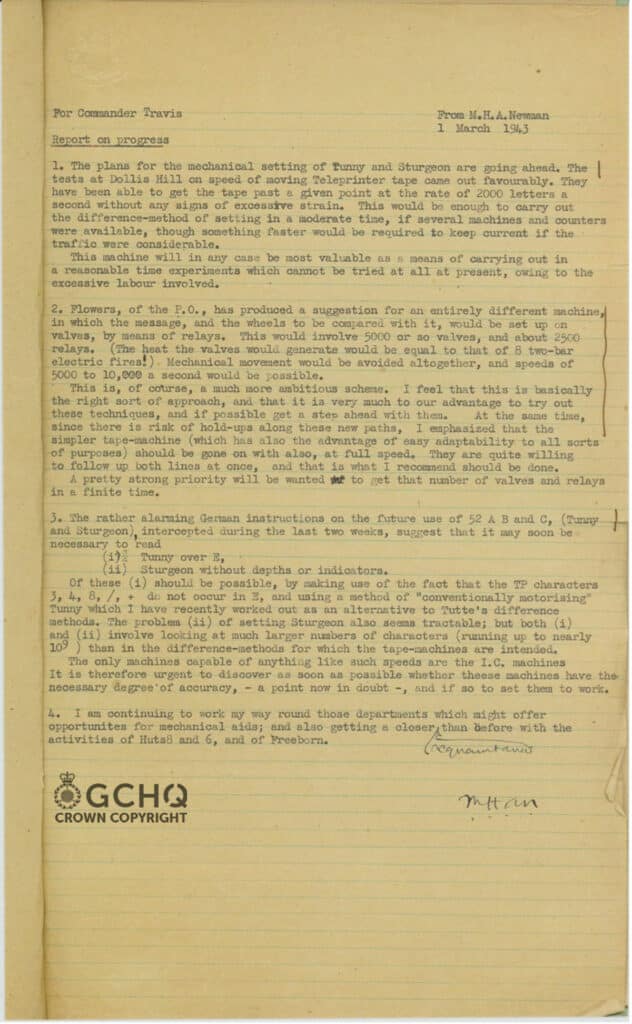

In one of the photographs, there is a letter that tracks the progress of deciphering communications between senior Nazis. The letter mentioned Thomas “Tommy” Flowers, the General Post Office engineer who designed Colossus to be built with off-the-shelf telephone exchange components. He was able to create such a complex machine using readily available parts.

“Colossus was perhaps the most important of the wartime code-breaking machines because it enabled the Allies to read strategic messages passing between the main German headquarters across Europe,” said Andrew Herbert OBE FREng, Chairman of Trustees at The National Museum of Computing, in a statement. “This is one of the many reasons we’re so proud to have a fully working reconstruction of a Colossus code-breaking machine on display at The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.”

“From a technical perspective, Colossus was an important precursor of the modern electronic digital computer, and many of those who used Colossus at Bletchley Park went on to become important pioneers and leaders of British computing in the decades following the war, often leading the world in their work. We are proud to join with GCHQ in celebrating this significant date in the Colossus legacy.”