Aerospace engineers at the University of Cincinnati are developing novel ways to reduce engine noise for the U.S. military and commercial aviation, both to keep the peace with airport neighbors and to protect the health of ground crews and service members. In this effort, the team has come up with a new nozzle design for F-18 fighter planes they hope will dampen the deafening roar of the engines without hindering performance.

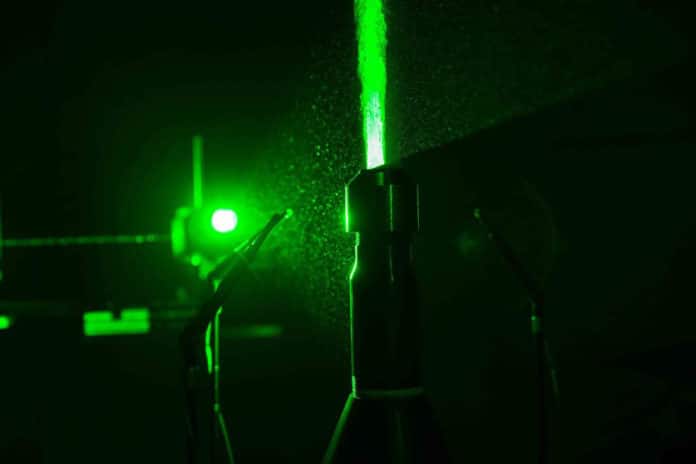

In tests performed inside an anechoic chamber – a room designed to completely absorb reflections of acoustic waves, engineers started by firing up a 1/28th-scale model of the F404 jet engine used in the F-18 fighter aircraft. The team can turn on fighter jet engines remotely outside the chamber and use lasers and other equipment to measure and analyze the noise and the exhaust plume from the engine.

The interior of the nozzles features triangular fins like rows of shark teeth that significantly reduced jet engine noise in UC lab tests. After some experimentation, the nozzle altered the exhaust flow in such a manner that it could reduce engine noise by between 5 and 8 decibels. That might not seem like much, but unlike linear scales like a ruler where an inch is always an inch, decibels are measured in a logarithmic scale in which 20 decibels is tenfold louder noise.

“That’s very significant,” said professor Ephraim Gutmark. “Typically, engine companies are happy even getting a half-decibel improvement because decibels represent a logarithmic scale.”

Besides, the engineers said the use of a nozzle would not negatively affect the performance of the engine. In fact, the noise reduction could allow fighter jets to last longer in a phenomenon called acoustic loading, in which the noise and vibrations can affect even the aircraft itself.

Jet noise, in particular, represents a serious health risk in military and commercial aviation. According to the Naval Research Advisory Committee, Navy personnel on flight decks are exposed to noise in excess of 150 decibels. Hearing loss and tinnitus are the leading causes of military disability claims.

UC engineers test their novel nozzle designs on both cold and heated jets with an exhaust that burns as hot as 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit. If the design works with this engine, it can be applied to any other engine with minor modification, Gutmark explained.

The project is a collaboration between UC, the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, and Naval Air Station Patuxent River. This fall, NAVAIR will test the UC designs and performance on F-18 Super Hornets, the tactical fighter plane used by the U.S. Marines and Navy.