In the Kochi prefecture of Japan, the company Hidaka Washi produces the world’s thinnest paper, called Tengujo, which is almost completely transparent on drying. Although the paper is extremely thin and almost transparent, it also offers serious durability with its long fibers.

About 1,000 years ago, workers created Tenjugo by hand that was used as curtains, tissue paper, decorated kimono – traditional Japanese garment. After that, the paper is used in typewriters. Over time, the paper became as thin as possible, using the machine rather than using the hands as before.

In 2014, Hiroyoshi Chinzei – director of Hidaka Washi – received orders from the National Archives of Japan: creating a Tengujo that weighs only 1.6g per meter. If successful, this Tengujo will be the thinnest paper in the world today. After two years of research, Hiroyoshi Chinzei was successful. Even Hidaka Washi Company also created a unique type of Tengujo, with a thickness of only 0.02mm, thinner than human skin, an achievement that no one in the world has been able to repeat.

How is Tengujo made?

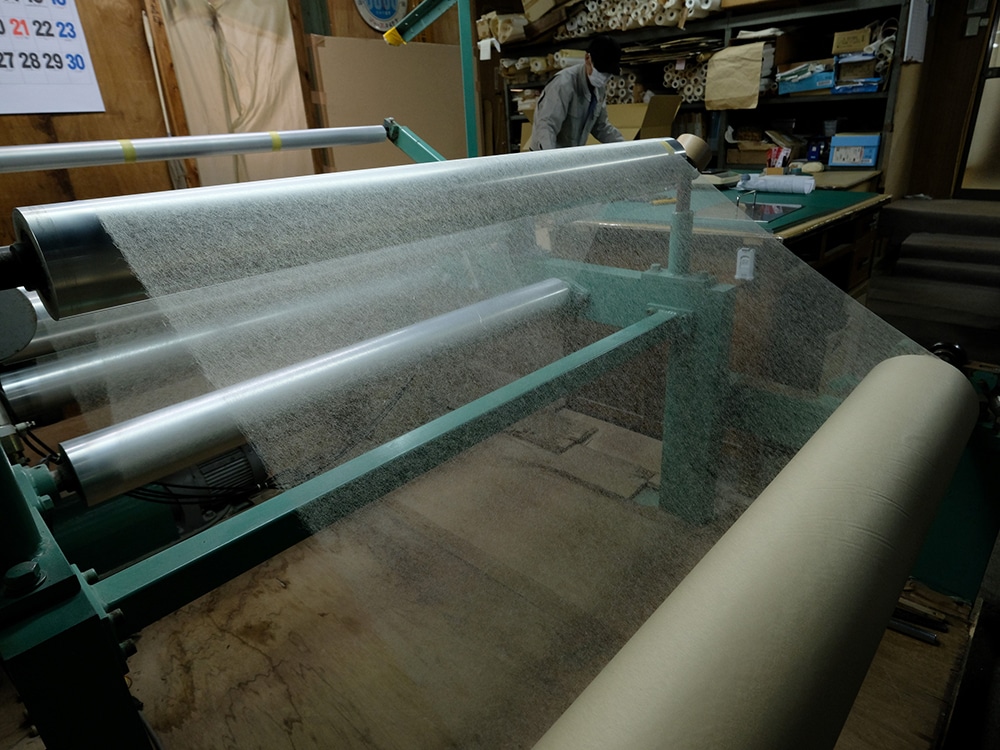

Tengujo is made from mulberry tree trunks (Kozo). The Japanese workers wash, remove the dust on the Kozo, and strip into small fibers. The material is then soaked in a water tank combined with Neri – a thick viscous liquid that is derived from the Tororo-Aoi plant, also known as sunset hibiscus. This process helps the Kozo fibers to be flexible, sticky, and easy to form into thinner fibers. This stage takes a lot of time, effort. Despite being industrialized, workers still used their hands during the critical period.

The skillful craftsmen turned the fiber into long white threads, which are then removed from the tub and spread out evenly over a screen, like a spider’s web. By the time the liquid dries, the fibers cling together, forming a thin, delicate yet interestingly durable sheet of paper.

According to Hiroyoshi Chinzei, this process is not a secret of any company, and it is easy to follow if you follow the rules and be careful.

Many people wonder what kind of tasks ultra-thin paper will do!

Currently, many Japanese companies can produce Tengujo so thin that it cannot be used for any writing or decoration purposes. Instead, the only and most important benefit of ultra-thin Tengujo is to protect other types of paper, especially ancient texts.

Choi Soyeon – an expert in document preservation at Yale University’s British Arts Center (USA) – said that documents, manuscripts, books, and newspapers are susceptible to corrosion over time. Therefore, experts really need a paper-like Tengujo to protect important documents.

Until now, Tengujo has become the first choice of major libraries and museums in the world such as the Louvre Museum (France), the Library of Congress, the British Museum and the British Art Center at Yale University (USA).