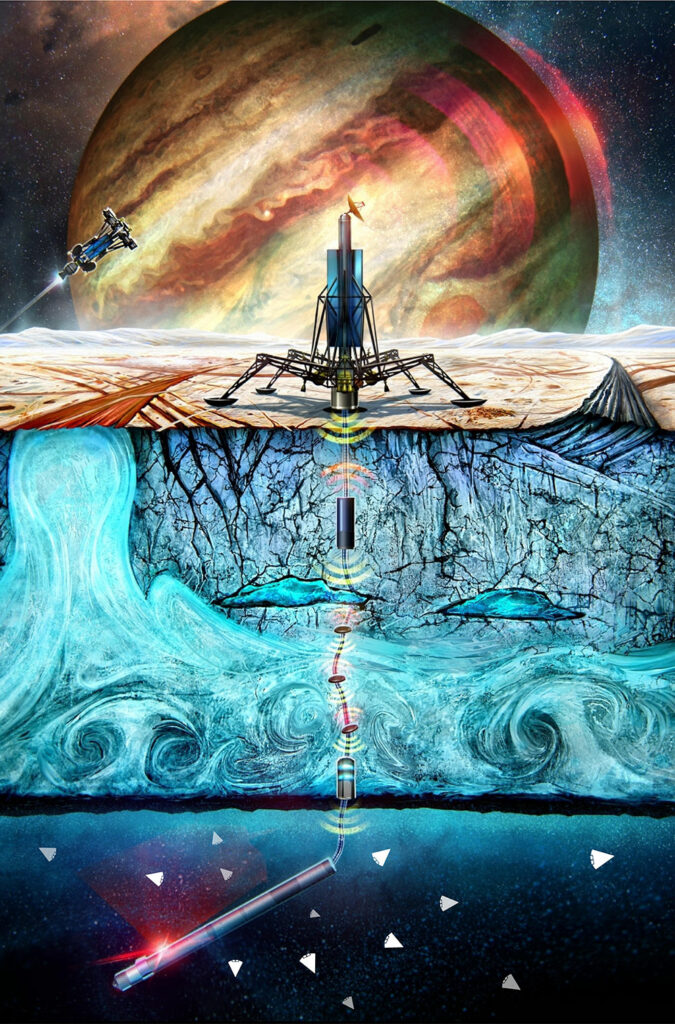

Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory are working to develop a swarm of cellphone-size swimming robots that could whisk through the water beneath the miles-thick icy shell of Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus, looking for signs of alien life. The tiny robots would be released underwater, swimming far from their mothercraft to take the measure of a new world.

Called Sensing With Independent Micro-Swimmers (SWIM), the concept has recently been awarded $600,000 in Phase II funding from the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. These mini-swimmers would be much smaller than other concepts for planetary ocean exploration robots, allowing many to be loaded compactly into an ice probe. They would add to the probe’s scientific reach and could increase the likelihood of detecting evidence of life while assessing potential habitability on a distant ocean-bearing celestial body.

The early-stage SWIM concept envisions wedge-shaped robots, each about 5 inches (12 centimeters) long and about 3 to 5 cubic inches (60 to 75 cubic centimeters) in volume. About four dozen of such robots could fit in a 4-inch-long (10-centimeter-long) section of a cryobot 10 inches (25 centimeters) in diameter, taking up just about 15% of the science payload allocation, allowing for more instruments to be carried onboard.

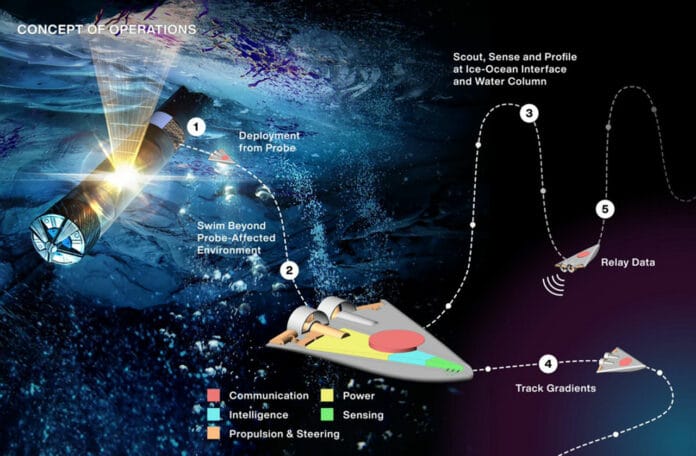

The SWIM robots would be connected via a communications tether to the surface-based lander, which would, in turn, be the point of contact with mission controllers on Earth. SWIM would also allow data to be gathered away from the cryobot’s blazing-hot nuclear battery, which the probe would rely on to melt a downward path through the ice. Once in the ocean, that heat from the battery would create a thermal bubble, slowly melting the ice above and potentially causing reactions that could change the water’s chemistry.

Each of these SWIM robots would have its own propulsion system, onboard computer, and ultrasound communications system, along with simple sensors for temperature, salinity, acidity, pressure, and chemical to monitor for biomarkers – signs of life.

The SWIM robots could “flock” together in a behavior inspired by fish or birds, thereby reducing errors in data through their overlapping measurements. That group data could also show gradients – temperature or salinity, for example, increasing across the swarm’s collective sensors and pointing toward the source of the signal they’re detecting.

“If there are energy gradients or chemical gradients, that’s how life can start to arise. We would need to get upstream from the cryobot to sense those,” said the concept designer, Ethan Schaler of NASA JPL.