Engineers at Duke University have developed a smart window-like technology that, with the flip of a switch, can alternate between harvesting heat from sunlight and allowing an object to cool. This new electrochromic technology – material that changes color or opacity when electricity is applied – could both heat and cool buildings if mounted on their outside walls.

Smart windows made from electrochromic glass are a relatively new technology that uses an electrochromic reaction to change glass from transparent to opaque and back again in the blink of an eye. These devices typically incorporate two thin, clear layers of electrodes, with an electrically responsive material sandwiched between them. The material is transparent by default but darkens when an electrical current flows between the electrode layers.

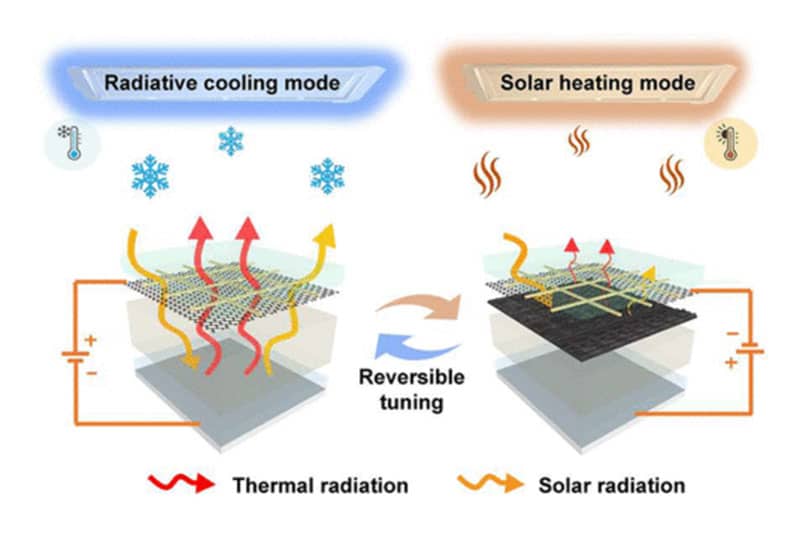

The new material developed by the Duke engineers also works in a similar fashion. It is composed of two electrode layers made of graphene, each one of which has a thin grid of gold deposited on one side to enhance its electrical conductivity. Between these two electrodes is a liquid electrolyte containing metal nanoparticles, and finally a mirror-like reflective material on the bottom.

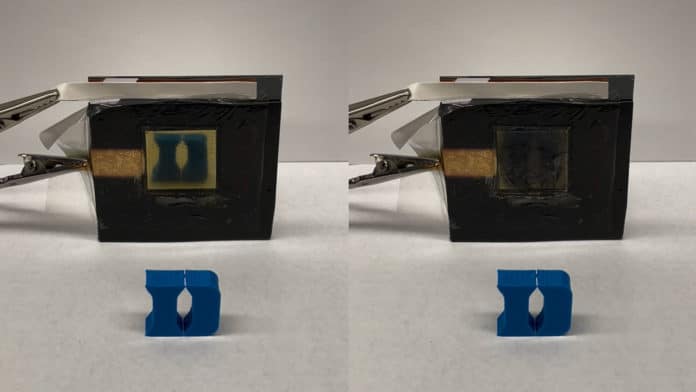

Researchers demonstrate a thin device that interacts with both spectrums of light while switching between passive heating and cooling modes. In the heating mode, the device darkens to absorb sunlight and stop mid-infrared light from escaping. And in the cooling mode, the darkened window-like layer clears, simultaneously revealing a mirror that reflects sunlight and allows mid-infrared light from behind the device to dissipate.

In the demonstration, electricity passing through the two electrodes causes metal nanoparticles to form near the top electrode. This causes the electrolyte to turn black and the entire device to absorb and trap both visible light and heat. And when the electrical flow is reversed, the nanoparticles dissolve back into the liquid, transparent electrolyte. The transition between the two states takes a minute or two to complete.

“The device would spend many hours in one state or the other out in the real world, so losing a couple of minutes of efficiency during the transition is just a drop in the bucket,” said Po-Chun Hsu, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke.

Researchers say there are still many challenges to making this electrochromic technology useful in everyday settings. The largest one might be increasing the number of times the nanoparticles can cycle between forming and disintegrating, as the prototype was only able to perform a couple of dozen transitions before losing efficiency.

However, as technology matures, there may be many applications for it. It might be applied to exterior walls or roofs to help heat and cool buildings while consuming very little energy.

“I can envision this sort of technology forming a sort of envelope or façade for buildings to passively heat and cool them, greatly reducing the amount of energy our HVAC systems have to consume,” Hsu said. “I’m confident in this work and think its future direction is very promising.”