The COVID-19 pandemic brought a complex array of challenges that had mental health repercussions for everyone, including children. Sometimes it can be difficult for children to open their hearts to adults.

A recent study by a team of roboticists, computer scientists, and psychiatrists from the University of Cambridge has suggested that robots can be better at detecting mental wellbeing issues in children than parent-reported or self-reported testing.

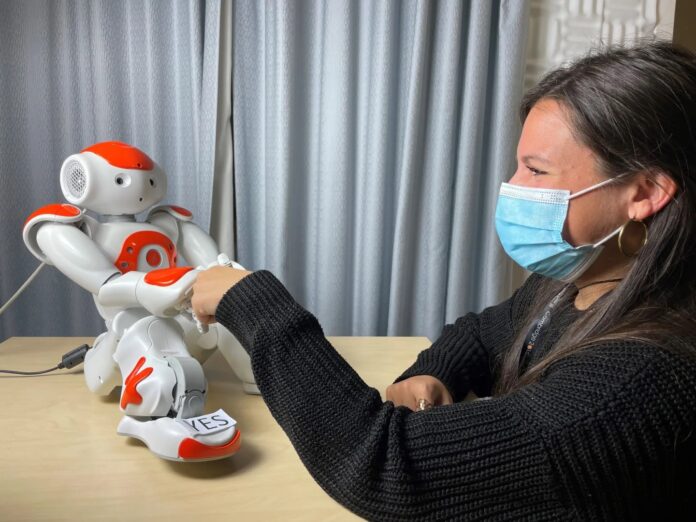

The team carried out an empirical study with 28 children 8-13 years old interacting with Nao – a humanoid robot about 60 centimeters tall – in a 45-minute session. The robot administered the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) to assess the mental wellbeing of each participant. A parent or guardian, along with the member of the research team, observed from an adjacent room.

Prior to the experimental session, the team also evaluated children’s mental wellbeing using established standardized approaches via online RCADS questionnaires filled by the children (self-report) and their parents (parent-report).

During each session, Nao, with a child-like voice, asked children open-ended questions about happy and sad memories over the last week, administered the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ), and also a questionnaire used in diagnosing anxiety, panic disorder, and low mood.

Researchers clustered the participants into three groups based on their SMFQ scores. The participants interacted with the robot throughout the session by speaking with it or by touching sensors on the robot’s hands and feet. Additional sensors tracked participants’ heartbeat, head, and eye movements during the session.

Further, researchers analyzed the questionnaire response across the three clusters and across the different modes of administration (self-report, parent-report, and robotized). The results show that the robotized evaluation seems to be the most suitable mode in identifying wellbeing-related anomalies in children across the three clusters of participants as compared with the self-report and parent-report modes. Children enjoyed talking with the robot; some shared information with the robot that they hadn’t shared either in person or on the online questionnaire.

“Since the robot we use is child-sized and completely non-threatening, children might see the robot as a confidante – they feel like they won’t get into trouble if they share secrets with it,” said Nida Itrat Abbasi, the study’s first author. “Other researchers have found that children are more likely to divulge private information – like that they’re being bullied, for example – to a robot than they would be to an adult.”

The researchers now hope to expand their survey in the future by including more participants and following them over time. They are also investigating whether similar results could be achieved if children interact with the robot via video chat.

Journal Reference:

- Abbasi, N., Spitale, M., Anderson, J., Ford, T., Jones, P., & Gunes, H. Can Robots Help in the Evaluation of Mental Wellbeing in Children? An Empirical Study. 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication. DOI: 10.17863/CAM.85817